Mars’ northern ice cap is young

Geophysical investigations reveal surprising results

To understand the properties of the rocky mantle beneath Earth's continents, researchers use a little geophysical trick: they measure how fast large areas of land, once covered by kilometres of ice during the last ice age around 20,000 years ago, continue to rise today. Thick ice sheets once depressed Earth's surface and, following their melting, it has slowly been rising. This process, known as glacial isostatic adjustment, is still observed in Scandinavia, where the surface rises by up to one centimetre per year, helping scientists to better understand our planet's composition. Until now, such phenomena have not been documented on other planets. Adrien Broquet from the German Aerospace Center (Deutsche Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR) gathered a group of leading scientists in planetary science and geosciences to document a comparable process occurring on Mars. Together, the group has been able to determine the Red Planet’s interior structure and assess the age of its northern polar ice cap.

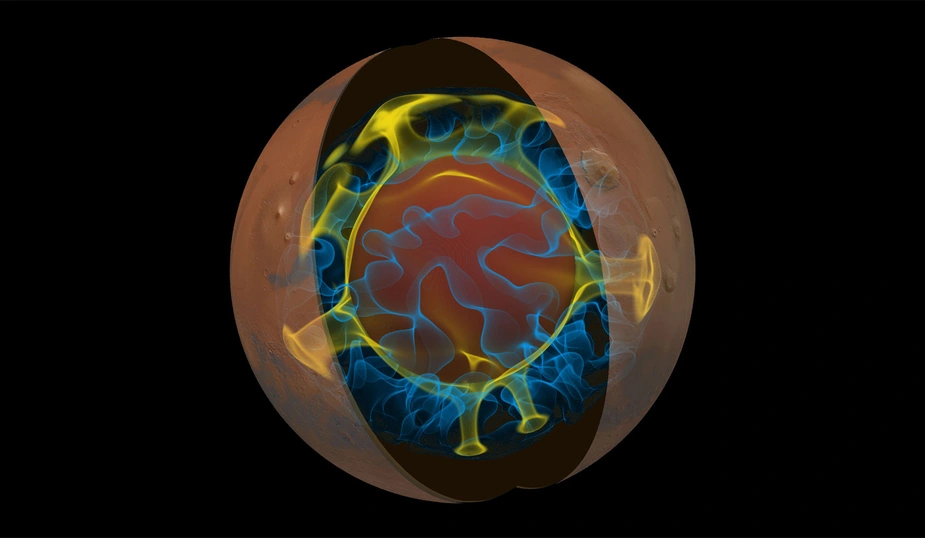

The north pole of Mars is covered by a 1000-kilometre-wide, three-kilometre-thick ice sheet composed mainly of pure water ice. "Estimating the deformations induced by the ice sheet at Mars's north pole is key to understanding the planet's interior structure," explains Adrien Broquet from DLR's Institute of Planetary Research. He and his colleagues investigated the formation of this ice sheet by combining geophysical models of Mars's thermal evolution with calculations of glacial isostatic adjustment, along with gravity, radar and seismic observations. The results of these analyses were published today in the journal Nature. "We show that the ice sheet pushes the underlying ground into the mantle at a rate of up to 0.13 millimetres per year," notes Broquet. “The small deformation rates indicate that the upper mantle of Mars is cold, highly viscous and much stiffer than Earth's upper mantle," comments Ana-Catalina Plesa, geophysicist at DLR and co-author of the study.

The last ice age provides insights into Earth's mantle dynamics

The surfaces of Earth and other rocky planets may appear proverbially 'rock solid', but events such as volcanic eruptions and earthquakes reveal that our planet is very much dynamic. Beneath the cold and stiff crust, rocky planets have a hot, deformable mantle. Whether it is the individual continental plates on Earth – lithospheric blocks drifting past each other like rafts – or the monolithic crust of Mars, the slow deformation of the underlying mantle brings these planets to isostatic equilibrium.

For over a century, researchers have studied Earth's isostatic balance by observing changing ice loads, from glaciers to ice caps, and how the planet's surface responds in turn. The rate at which deformation occurs has helped scientists estimate Earth's internal properties, as well as the shape and extent of past ice sheets that once covered a large portion of the planet. In 2002, two satellites were launched to investigate this deformation process as part of the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE). This joint NASA and DLR mission investigated Earth's deformation by measuring variations in our planet’s gravitational field, the mission continues with its successors GRACE-FO and the upcoming GRACE-C. "Observing and understanding glacial isostatic adjustment has been pivotal in Earth sciences, but thus far, such observations were limited to our planet," explains Broquet.

As viscous as bird glue

The isostatic adjustment process heavily depends on a planet's internal structure and properties, and particularly on viscosity – a measure of how much materials resist flowing. Viscosity depends on both the type of material and its temperature. Honey and plastic, for example, deform more easily when warm and become stiffer (have a higher viscosity) at lower temperatures. The word viscosity originates from the viscous juice of mistletoe berries (viscum), from which sticky, viscous bird glue was once made for catching birds. Hence, viscous means 'as viscous as bird glue'. For comparison, the rocks making up Earth's mantle are over one trillion (twelve zeroes) times more viscous than asphalt, but still deform and flow over geological timescales.

Mars's mantle is 10 to 100 times more viscous than Earth's

Radar sounders aboard ESA's Mars Express (2003) and NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (2005) mapped Mars's north polar cap, revealing the interface between the ice and underlying bedrock. Surprisingly, while large ice-sheets substantially depressed Earth's surface 20,000 years ago, Mars's surface appears undeformed by its large mass of ice. Why the surface of Mars has remained so stiff and undeformed has been unclear for decades.

By combining radar data, estimates of Mars's variable gravity field, and seismic measurements collected by the InSight lander, Broquet and his colleagues discovered that the key to this conundrum is time. The interior of Mars is so viscous and cold that the surface has not had the time to fully deform. Using numerical simulations, Broquet's group estimates that Mars's north pole is currently subsiding at rates of up to 0.13 millimetres per year. This requires the viscosity of Mars's upper mantle to be 10 to 100 times greater than Earth's, indicating that the interior of the Red Planet is extremely cold. "Although the mantle underneath Mars's north pole is estimated to be cold, our models are still able to predict the presence of local melt zones in the mantle near the equator," comments Doris Breuer, another co-author of the DLR study. Indeed, the interior of Mars is full of surprises, with a seemingly cold north pole and the recently volcanically active equatorial regions.

The ice sheet covering Mars's north pole must also be substantially younger than any other large-scale feature seen on the planet. With an estimated age of 2 to 12 million years, it may well be the youngest and largest feature on the Red Planet.

The work of Broquet and his colleagues is the first to document glacial isostatic adjustment on another planet, and has profound implications for understanding Mars's interior and geological evolution. In recent years, multiple GRACE-like gravity missions have been proposed for Mars, including Oracle and MaQuIs. In addition to studying the planet's climate, future gravity missions will now have a new goal: providing new measurements of Mars's rise and fall.

Related links

- DLR Institute of Planetary Research

- Published in the journal Nature

- DLR's Mars Express mission page

- DLR's InSight mission page

- DLR news – GRACE-C – German-US-American environmental mission has been extended

Contact

German Aerospace Center (DLR)

Institute of Planetary Research

Rutherfordstraße 2, 12489 Berlin

Anja Philipp

Corporate Communications Berlin, Neustrelitz, Dresden, Jena, Cottbus/Zittau

+49 30 67055 8034

www.dlr.de/berlin

Press release DLR, 26 February 2025